Engineering Change Order (ECO)

What is an ECN or ECO in Manufacturing?

They say the only thing constant is change – and the manufacturing process is no exception. Although equipment, standards, and procedures take a good deal of planning to establish, they are not set in stone. Machines and electrical components evolve as they move towards newer models, while standards and procedures are improving all the time.

Rather than resist, organizations can benefit more from adapting to change. In most cases, changes will need to undergo a thorough review. This ensures that new parts or modifications are fit for purpose, as well as compatible with existing components and processes. These suitability assessments are executed through an Engineering Change Notice (ECN) or Engineering Change Order (ECO).

An ECN or ECO documents the details about a process or system change. They indicate the component or process that is being modified, the cause of change, and a full description of the issue. It lists components and processes that would be impacted, as well as technical drawings and documents for reference. An ECN or ECO also clearly shows the approvals obtained to carry out any further action.

What are the steps of an engineering change process?

Organizations may have varying engineering change management processes to suit their specific needs. However, the general steps will look similar for the most part. Whatever the industry or the company is, change processes generally require three types of documents – a request, an order, and a notification. See the following steps showing how these documents relate to each other:

1. Identify the problem and the scope

The process starts off by recognizing an issue that needs to undergo change. Part of this stage also defines the extent of the change. A high-level assessment of the number of affected parts and the corresponding amount of work begins at this stage.

2. Create an Engineering Change Request (ECR)

An ECR is then raised to go into more detail about the proposal. This stage prepares the information that would later equip stakeholders to make a decision on whether to proceed or not.

This process explains the technical feasibility of replacement components or process revisions. For example, when changing out a discontinued model, differences in specifications are compared and any impacted auxiliary parts are specified.

This stage also determines the costs and benefits of going through the change. The resources required to implement new processes are listed, while any associated risks are likewise identified.

3. Review and approve the ECR

The ECR then proceeds to a review and approval process. It is sent out to a committee that makes the “go” or “no-go” decision. As with most review and approval processes, this stage is potentially iterative, with the final request being modified as needed.

4. Create an Engineering Change Order (ECO)

Now that the ECR has been reviewed and approved, the ECO is then created. If an ECR sums up the information required to guide approvals, think of the ECO as the handbook to implement the changes.

The ECO provides all the information required to execute changes effectively. Generally, this includes updated technical drawings, task lists, and BOMs. The ECO would list out all equipment assemblies that are impacted, as well as the relevant procedure manuals that are required to execute any change tasks. By creating a methodical ECO, risks of miss-outs can be avoided.

5. Review and approve the ECO

After completing the ECO, it then goes through another round of review and approval. Given the possibly wide scope of work, approvals could come from a number of different individuals with their own respective areas of expertise. After the stakeholders have provided their endorsement, senior management can finally sign off the overall approval.

6. Communicate the Engineering Change Notice (ECN) to relevant groups

With the ECO reviewed and approved, a notification will then be sent out to all relevant groups. The ECN provides details of the change approval and steps that would shortly need to take place. It is important to ensure that the ECN is communicated across all individuals who are affected by the change.

7. Implement the required change

Now that the engineering change proposal has gone through the steps and all relevant reviews and approvals, implementation can commence. Each team is given their specific roles and responsibilities to implement the required changes. At this point, the ECO and ECN become essential documents to guide the execution of tasks.

Who creates Engineering Change Orders?

Anyone who identifies required changes to catalogued materials and has access to the system is able to raise an ECO. The review and approval process, however, is usually performed by a different individual. Additional oversight allows for a more impartial check and balance system.

What are some types of changes that require ECOs?

First, you should identify the type of change. This information will equip you to determine the level of review and approval that will go in the process.

You can also associate the depth of assessment with the different types of changes. Here are a few common examples:

1. Typographical changes

These types of changes are all about spelling corrections and typographical errors. There are no physical changes that occur to any of the components, and therefore no effect on the system’s form, fit, or function.

2. Alternative manufacturers

Sourcing from another manufacturer or supplier should not affect the operation of existing equipment. These changes usually seek to improve the procurement process by reducing lead times or costs. For this type, it is important to ensure that only the source of supply changes, and not the specifications of the part itself.

3. Obsolete component

As much as possible, replacing a manufacturer-discontinued part does not intend to change the characteristics of existing components. However, since an entirely new component is being introduced, more thorough compatibility reviews are necessary.

4. Design changes and new models

These types of changes are usually identified as opportunities to improve the current process. As a result of modifications to the form, fit, and function of an existing system, these usually undergo more comprehensive reviews.

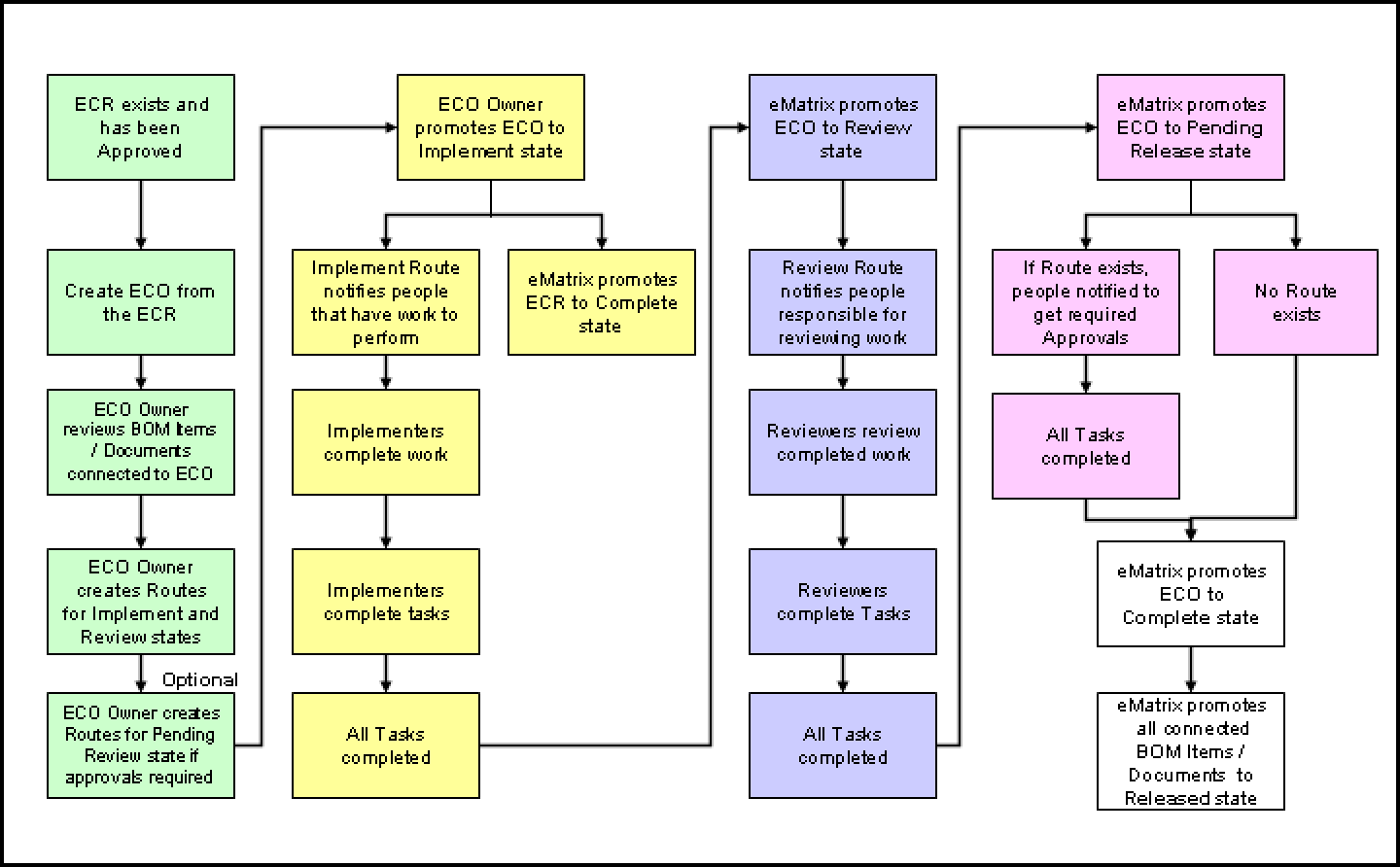

What does a typical engineering change process diagram look like?

While we have previously mentioned the steps that a change proposal goes through, we only focused on how a request reaches the implementation stage. The reality is that a lot more activity happens in the background after generating an ECN.

Implementation tasks, for example, can be allocated to a number of groups and individuals. This becomes complicated to track given that each task needs to be reviewed for completion and updated accordingly. Assets will need to be updated in a CMMS, along with any other maintenance work associated with the change management.

A typical ECO process for existing equipment within the plant may resemble the following diagram:

What are the signs of an ECN/ECO bottleneck?

A process “bottleneck” is regarded as an activity that contributes most to the lead time of a particular operation. In other words, bottlenecks are constraints within a process that cause delays. Change management processes can take a lot of time and effort to complete. For that reason, organizations need to be aware if their queues are getting out of hand. When overlooked, delayed ECN/ECO implementation can cause devastating blows to production and safety objectives.

Here are some signs that your ECN/ECO queue is causing constraints to the rest of your operations:

1. Redundant information flows

The request and implementation of any change are only as good as the information available. If you are receiving multiple requests, and seeing a lot of double-ups, then you might be wasting a lot of your resources. Have a clear way of receiving information that you can align with your departments.

2. Disorganized ECO information

Continuing from our first point, it doesn’t help to carry out ECOs if your supporting documents are unavailable. Use your CMMS as a repository of technical documents, drawings, and manuals.

3. Poor accountability of Engineering Change Order tasks

A well-written document can only be useful to the organization if executed well. One of the pitfalls of ECO implementation is when roles and accountabilities are not clearly stated. For change management success, each group must know their contribution to the collective effort.

4. Delayed resolution due to unnecessary and/or manual coordination

Change processes typically affect a number of teams and departments. Without clear communication lines across the organization comes a higher likelihood of unnecessary coordination between working groups. A more efficient practice is to communicate through a system by which teams can read and update each other’s progress in real-time. Harnessing tools like CMMS software helps facilitate group collaboration.

5. Inefficient handling of paper documents

As we all have experienced, going digital cuts manual processing by a considerable amount. In a time when even maintenance software is available on mobile devices, choosing to work with a literal paper trail becomes harder to justify.

What are the Four Principles of ECO Management?

Engineering change order presents a real opportunity to improve existing processes and procedures. The downside is that there are certain costs to implement changes properly. The idea is to minimize the negative effects of an ECO and highlight its benefits.

1. Avoid unnecessary changes

New products can easily look very promising at first. Who wouldn’t want a fresh set of components with promises of higher production efficiencies? The harsh reality is that needlessly moving to new products can actually cause more harm than good. Cost savings from new developments might not outweigh the costs of retooling investment and compatibility adjustments.

Some key points to consider when evaluating the need for change are the return on investment and the urgency of the requirement. For a new product development that pays back within a year, for example, then financial risks might actually be low enough to consider pursuing. As for urgency, assess whether the change merely fine-tunes your current processes or significantly impacts your key operating procedures.

2. Reduce the impact of change

The second principle leans more towards accepting that change is inevitable. The next best thing is then to reduce the impact of change.

Imagine a system of components that are interdependent with each other. If one of the components becomes obsolete and is replaced with a new part, will the system still be operational? How many other components will you need to change out because of that one part that changed? This example illustrates that the impact of change can be addressed at the design level of the whole system.

If the sub-assemblies of your overall system are more modular in design, then you are setting yourself up to reduce the impact of change. You want your overall system to comprise of self-contained groups that are to some extent independent of adjacent subsystems.

3. Detect Engineering Change Orders early

The longer ECOs are pushed back and delayed, the harder they are to accomplish. By continuing to run a suboptimal process, you are less likely to reverse the negative effects on your equipment and operations. It helps to detect ECOs early and to implement the necessary changes before any further damage is done.

A variation of this principle is done using simulation technology to replicate the effects of long-term operations. By combining simulations of usage patterns and the analysis of potential failure modes, the right smarts can be applied to get ahead of change requirements.

4. Speed up the Engineering Change Order process

The previous principles were focusing on the design and engineering aspects of ECOs. The last principle is a bit different, as it focuses more on the importance of enforcing the process.

ECOs are vulnerable to administrative delays, as are most processes. The actual time it takes to complete a change order will unsurprisingly be longer than the actual working hours that have been spent to execute related tasks. Sources of delay should be identified and minimized, particularly nonessentials such as waiting time, idle time, and time spent on redundant activities.

How can automation help the ECN/ECO process?

A sizable portion of issues when implementing an ECN/ECO process is related to the way requests flow from one stakeholder to another. To name a few - communication between stakeholders, visibility of progress, availability of information, and accuracy of the data. All of these points, and more, can effectively be addressed by automating the process wherever applicable.

For example, any process that requires the input of a person is subject to the risk of human error. Anything from typographical errors to miss-outs can easily be attributed to manual updating. By automating parts of the process, such as workflow generation, tasks can be programmed to go through all the required steps as designed. Also, since all the information is available on the system, transparency on the progress of tasks can be easily achieved.

Conclusion

Change management processes are essential tools for an organization to keep working in tip-top condition. By having a method of implementing change, risks of any miscalculated decisions are minimized if not eliminated. While change management is a meticulous process, technological tools are readily available to ease the burden of what used to be a purely manual approach.

Want to keep reading?

Engineering Change Notice (ECN)

Engineering Change Order (ECO)

What Should Reliability Engineers Do? What Should They Learn? What Skills Should They Have?

4,000+ COMPANIES RELY ON ASSET OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT

Leading the Way to a Better Future for Maintenance and Reliability

Your asset and equipment data doesn't belong in a silo. UpKeep makes it simple to see where everything stands, all in one place. That means less guesswork and more time to focus on what matters.

![[Review Badge] GetApp CMMS 2022 (Dark)](https://www.datocms-assets.com/38028/1673900459-get-app-logo-dark.png?auto=compress&fm=webp&w=347)

![[Review Badge] Gartner Peer Insights (Dark)](https://www.datocms-assets.com/38028/1673900494-gartner-logo-dark.png?auto=compress&fm=webp&w=336)

An engineering change order (ECO) or an engineering change notice (ECN) is a document that begins the process for making adaptations or corrections during a product’s lifecycle. It plays a critical role in engineering and product development.