How to Improve Food Safety Behaviors at Your Plant

Many food manufacturing companies presume (and hope) that the Safe Quality Food (SQF) program will certify that their food is safe and of high quality. The SQF program is one of many different certified programs to satisfy the food safety requirements of the Global Food Safety Initiative. Hence, a very common approach is to follow the SQF code line by line to generate appropriate standard operating procedures and document templates. These documents are then filled out by employees in real-time to “prove” that the food must therefore be safe.

Although these steps are necessary, they are woefully insufficient without a systematic approach to achieving consistent, self-improving food safety behaviors in the plant. This is why the SQF program is not an end in itself. Rather, it’s a means to an end: sustainable behaviors which ensure that the food is safe, drive cross-functional goals and training, and allow even better food safety behaviors to become a habit.

Documentation provides the bookends to these behaviors. And even without complete and thorough documentation, improved behaviors are still the right thing to do in order to keep the food safe.

A Common SQF Approach

I have many decades of food manufacturing experience leading food safety and quality teams. During that time, I have seen the SQF scheme applied from rookie organizations (no food safety plan or process in place) to veteran organizations (successful SQF audits across many years). I have also seen the SQF process applied from very dry products (powder blends) to very wet products (juices). In each situation, the common mindset was a laser-sharp focus on developing standard operating procedures, and subsequent documenting (monitoring, verifying, validating) in order to prove that each step in the SQF code was being followed.

If something was not written down, it did not happen. This regulatory principle drives the documentation mindset. It’s one that is easily accepted and understood by everyone in the organization, across all levels and functions. However, this ease of acceptance can be the very thing which gets in the way of changing behaviors! This is a mindset of, "If the documents are in place, then we must be doing the right things." Of course, this is not sufficient.

Another commonality I have experienced is that it is easy to let the Quality Assurance team lead the SQF effort independently. “Get it done and report back when finished.” As long as the company gets good scores, everything must be ok. But if scores start falling and/or issues keep occurring, whose fault is it?

The Need for Documentation

Food safety documents must be thorough, accurate, and effective. Not having proof of a manufacturing step or a verification measurement can be a death knell (e.g., recall, regulatory action, etc.). Thus, documents are essential; this article is not intended to say otherwise. And since everyone needs to embrace food safety, not just Quality Assurance, this also applies to documentation. Standard operating procedures need buy-in from everyone in the organization who plays a role in the information being documented. Not gaining buy-in to something as straightforward as a standard operating procedure correlates strongly with making it impossible to drive any behavior changes.

SQF and Regulatory Demands for Behavior Change

Even though the rules seem to state that food safety is all about documentation, on a principles basis, all of the regulations and guidelines point instead to a requirement for behavior change. Some examples follow (emphasis added):

- SQF Food Safety Code for Manufacturing: For "Management Commitment,” the code has a mandatory element that the company "continually improve its food safety management system." Note the use of the word system, not documentation. Similarly, the code requires that senior management "ensure food safety practices…are adopted and maintained." Again, note the use of the word practices, not documentation.

- A Culture of Food Safety: A Position Paper from the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI): This entire treatise from the GFSI food safety culture working group (April 2018) is based on food safety culture being defined as "the shared values, beliefs, and norms that affect mind-set and behaviour..."

- Ready-to-Eat Seafood Pathogen Control Guidance Manual: This guidance from the National Fisheries Institute (March 2019) relates to preventing issues with seafood products. In the manual, it’s stated that "...the primary cause of contamination is Good Manufacturing Practices/sanitation..."

- Draft Guidance for Industry: Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food (January 2018): The FDA defines preventive controls broadly: "…procedures, practices, and processes." These three "P" words cover far more than just documents!

- 17 CFR 117.135: The Good Manufacturing Practices, as published in the Code of Federal Regulations, specify that preventive controls require an underlying systemic approach. For example, each of the mandatory preventive controls (e.g., process, food allergen, sanitation) start with the phrase "...controls include procedures, practices, and processes..." Documentation is assumed, not explicitly stated in this section.

The Need for Behavior Change and Improvement

A basic tenet of this article is that behavior must be changed in order to make a real difference with food safety practices, control, and outcomes. This requires the proper organizational mindset. Leaving potential change in the hands of only the Quality Assurance team will not work in the long run. Simply telling employees to follow updated standard operating procedures will not work either.

To borrow a concept from psychologist Carol Dweck, the organization, starting with senior management, needs to adopt a “growth mindset.” That is, believing that the organization can improve. She contrasts this with a “fixed mindset,” where we assume that we can’t change in any meaningful way. Dweck explains this in terms of people and parents, yet maintains that these principles apply equally to organizations.

As another example, consider the concepts of micro-optimization versus macro-optimization. A given function like Quality Assurance can do everything in its power to be superb at checking quality and ensuring that Good Manufacturing Practices are followed by employees. Similarly, another function like Sanitation can, in parallel, also do everything possible to ensure that its workers are handling chemicals safely and following manufacturers' recommendations for chemical contact time.

Both of these are examples of micro-optimization, i.e., optimizing the inputs and outputs of single functions independent of other functions. But whose job is it to identify the piece of equipment with the highest risk, and to ensure that it is cleaned and sanitized properly?

By contrast, the key leadership in a company focuses on optimizing the inputs and outputs of the entire organization in order to meet stakeholder needs (e.g., profits, consumer complaints, service). Optimizing the "macro" may even come at the expense of the optimization of a "micro.” In the context of continuous improvement of food safety behaviors, this may mean that decreased food safety risk requires more time from Production to execute certain line changeovers that minimize risk of allergen exposure. This runs counter to the typical Production mindset (i.e., pounds per hour) but aligns perfectly with ensuring that the final product is safe.

Lessons From Companies Who “Got It”

Next will be proven principles that were developed and used by food manufacturers who all had significant yet different SQF issues, but turned it around with meaningful behavioral solutions. I draw from three of the organizations that I had the gracious opportunity to be immersed in. Hence, all of these lessons are based on my personal experience of being in the trenches and enduring the stresses of improving food safety.

Here is an overview of the three different organizations:

- The first was a rookie organization that had never used a Global Food Safety Initiative scheme before. The organization chose SQF, and hired a SQF Coordinator to write the standard operating procedures and train everyone on them. They failed their first gap audit miserably.

- The second was a veteran organization that received good SQF scores across multiple plants year after year. However, overall scores were not increasing, and some plants were even seeing their scores decrease.

- The third was a veteran organization that also received good SQF scores in the past. But in the last five years, it found itself with scores decreasing every year, so that now they were at risk of surveillance audits. This was a classic case of leadership wanting just the Quality Assurance team to be responsible for the SQF audit, while the rest of the organization kept doing what it was supposed to be doing (e.g., pounds per hour).

Each of these organizations turned their SQF scores around with some similar, and some different, principles and approaches. In each case, improving food safety behaviors took close to two years. Here are the principles that led to success:

-

Have Patience

Changing employee behaviors takes time, and then it takes additional time for the results to be manifested. This could take up to two audit cycles, even with all due urgency.

-

Build Cross-Functional Food Safety Teams

Food safety and quality improvements cannot be driven solely by the Quality Assurance team. Assuming they can do it all is a road to perdition. Implementing behavioral changes in functional silos might optimize the "micro" but will fail at optimizing the "macro." This is especially true if Quality Assurance is not directly reporting to top leadership in the company and/or if they’re not forthcoming with a truthful representation of the state of affairs on the plant floor. The latter is insidious, as company leadership could easily be fooled into thinking that food safety risks are minimal when they are seeing relatively high SQF scores. In this regard, it’s a huge warning sign when scores are clearly decreasing year after year.

-

Build Cross-Functional Corporate Leadership

Similarly, although Quality Assurance can lead the overall food safety team—and it probably should—other functional leaders of the organization (e.g., Production, Maintenance, Purchasing) need to be actively involved. The best results are achieved when the CEO/president holds all of these leaders accountable for improved food safety results and when the CEO/president is personally involved.

-

Do Not Focus on the SQF Scores

The real goal is to identify food safety risks and decrease them. The way to do this is by focusing on the behaviors that need to be in place. Standard operating procedures, documentation, execution, and results will follow, as will improved SQF scores. Please note, a one or two point difference in the SQF score on any given year, one way or the other, does not mean that the underlying systems and behaviors are any better or worse. Keeping a focus on risks and proper behaviors will let you sleep at night, knowing that scores will consistently be in the 90s no matter what.

-

Maximize Plant-to-Plant Consistencies

For companies with multiple plants, ensuring that all plants are putting food safety actions into place consistently is extremely important. If plants are allowed to develop their programs independently—which is a common practice since each plant is indeed different in product mix, equipment, infrastructure, and the like—then by definition, best practices are not being reapplied across the corporation. Solutions to this include forming a Food Safety Team consisting of appropriate members from each plant, no matter the size or how "different" they claim to be.

Another solution is creating a Corporate Food Safety Team, which services each plant with common standard operating procedures and accountabilities. Said another way, if each plant is allowed to operate their food safety system independently, then they might optimize the micro, likely at the expense of optimizing the macro.

Conclusion

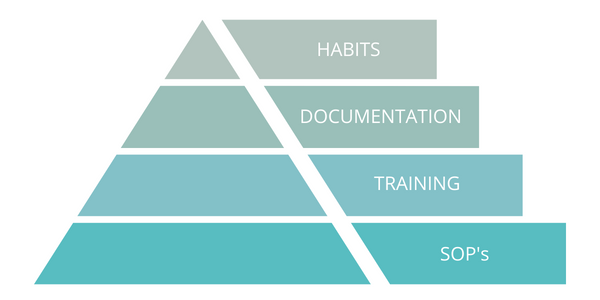

This is not easy work. It's actually so much easier to revert to generating or changing standard operating procedures. However, changing behaviors one step at a time rather than getting overwhelmed by trying to change everything immediately will lead to success. The pyramid below provides a visual representation:

- That appropriate risk-based standard operating procedures are the basis for action in a plant

- That these standard operating procedures are effective only if employees are properly trained and retrained

- That the training is only effective if employees are documenting the right things at the right time, per the standard operating procedures.

If all of this happens effectively, then behaviors are improved and new habits are created. Processes and procedures will only succeed when behavior and the resultant company culture support them.

Documentation of food safety processes and procedures is critical to minimizing regulatory risk. Equally important, if not more so, is aligning standard operating procedure development with the leadership necessary to change behaviors in the plant across all functions.

Driving improved behaviors into beneficial habits is tantamount to decreasing food safety risk. Lower risk means everyone sleeps better at night, including the ultimate consumer of the food.

Author bio:

Bob Lijana is a Food Safety and Quality Assurance Consultant with 35+ years of practical plant experience in food quality and food safety risk management—in concert with driving improved employee behaviors and plant profitability. He has hands-on experience with RTE products (refrigerated foods), prepared foods (cooked foods), and pasteurized juices; excellent technical understanding of microbiology (including pathogens such as Listeria), environmental monitoring programs, sanitation, and food science; involvement with regulated products over entire career, including GMPs, HACCP, SQF, FSMA, and a wide variety of corporate quality systems. Bob is an experienced writer to handle USDA and FDA issues, with 30 publications.

Want to keep reading?

What Should Be Included in a Food Safety Program?

Developing an Equipment Maintenance Program in Food Manufacturing

Maintenance in the Food Manufacturing Industry

4,000+ COMPANIES RELY ON ASSET OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT

Leading the Way to a Better Future for Maintenance and Reliability

Your asset and equipment data doesn't belong in a silo. UpKeep makes it simple to see where everything stands, all in one place. That means less guesswork and more time to focus on what matters.

![[Review Badge] Gartner Peer Insights (Dark)](https://www.datocms-assets.com/38028/1673900494-gartner-logo-dark.png?auto=compress&fm=webp&w=336)